City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York

544 U.S. 197

In March 2005, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down a decision in City of Sherrill, New York v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York. Sherrill is a case about land rights and sovereignty, and it raises the question what it means for an Indigenous nation to appeal to its colonizer to recognize its sovereignty over land that belonged to it before it was colonized.

City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation is a case about whether the Oneida nation had sovereignty over reaquired land within its historic reservation. In 1997 and 1998, the Oneida used profits from its Turning Stone casino to purchase separate parcels of land in petitioner City of Sherrill, New York in an open market transaction. The Oneida purchased 17,000 acres of land, scattered across two counties in Upstate New York, where they operate commercial enterprises: a gasoline station, a convenience store, and a textile facility. These properties, once contained within the historic Oneida reservation, were last possessed by the Oneida as a tribal entity in 1805. Nevertheless, the Oneida claimed to have revived its sovereignty over these parcels of land, and therefore they claimed to be immune from taxation. The City of Sherrill levied property taxes anyway, which the Oneida refused to pay. In response, the city sought to foreclose and assume title to these properties.

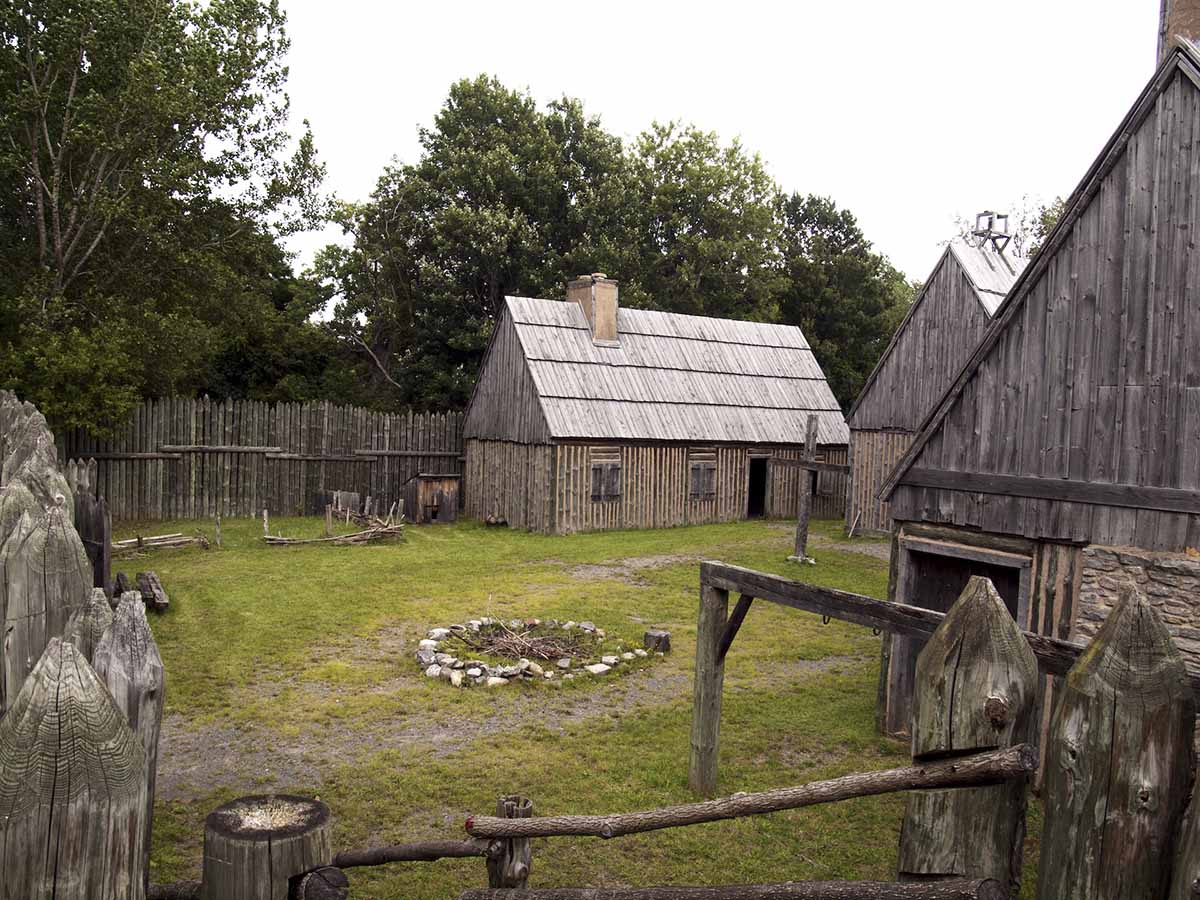

The Court’s decision provides us with the historical background of this case. The Oneida Indian Nation of New York is a direct descendant of the Oneida Nation, whose homeland comprised some six million acres in what is known now as central New York State. In 1788, the State and the Oneida entered into a treaty whereby the State purchased all of the Oneida’s lands, retaining a reservation of only three-hundred thousand acres for their own use. The Oneida does not contest the legitimacy of this treaty or the boundaries of the reservation. In 1790, Congress passed the first Indian Trade and Intercourse Act (commonly known as the Nonintercourse Act), barring sales of Indigenous land without the federal government’s acquiescence. Four years later, in the 1794 Treaty of Canandaigua, the United States acknowledged the Oneida’s three-hundred-thousand-acre reservation and guaranteed their “free use and enjoyment” of the reserved territory, and the Oneida agreed to never claim any other lands within the U.S. territory. Nevertheless, New York continued to purchase reservation lands from the Oneidas, and although the Washington administration objected, later administrations did not, and the federal government pursued a policy designed to open reservation lands to white settlers and to remove Indigenous peoples westward. Pressured by the removal policy, many Oneidas left New York, selling most of the remaining land as they left, and by 1920, the New York Oneidas retained only thirty-two acres in the State. The purchase of the reservation lands by New York State was recognized as illegal by the Court in a previous decision. The region was governed by the state and its county and municipal units since 1805, and almost all of its population was non-Indigenous.

In our case, the Oneida resisted the payment of property taxes assessed by Sherrill on the ground that its acquisition of parcels of historic reservation land revived the Oneida’s sovereignty piecemeal over each parcel, so that regulatory authority over the newly purchased properties no longer resides in Sherrill. The Court held that the Oneida is prevented from unilaterally reviving its sovereignty, in whole or in part, over the parcels at issue. “The Oneidas long ago relinquished reins of government and cannot regain them through open-market purchases from current titleholders,” writes Justice Ginsburg in her majority opinion which 8 out of 9 Supreme Court Justices signed. The Court offers two main reasons:

-

The distinct non-Indigenous character of central New York and its inhabitants;

-

The Oneida’s long delay in seeking judicial relief against parties other than the United States.

Ginsburg writes about the impracticability of returning to Indigenous control land that generations earlier passed into numerous private hands. The unilateral reestablishment of present and future Indigenous sovereign control, even over land purchased at the market price, would have disruptive practical consequences: Sherrill and the surrounding area are today overwhelmingly populated by non-Indigenous residents, and “a checkerboard of state and tribal jurisdiction” – created unilaterally at the Oneida’s behest – would seriously burden the administration of State and local governments and would adversely affect landowners neighboring the tribal patches.

Let us consider the Court’s primary reasons for its ruling. The Court rejects the Oneida’s claim to sovereignty because of the long time that has passed since they last owned the land, and since during this time – two centuries – the Oneida failed to seek U.S. courts’ recognition of its sovereignty over it. What would it mean for an Indigenous nation to use its colonizer’s legal system to protest against its colonization? First and foremost, it would mean acknowledging the state-sovereignty of the U.S. The Oneida’s refusal to pay property taxes, on the other hand, is a more creative form of resistance; trying in this way to unilaterally revive sovereignty over the land avoids the problem of acknowledging the sovereignty of the U.S. through recognizing the court’s jurisdiction. Indeed, it could be said to amount to a denial of U.S. sovereignty over the historic reservation. Alas, the Oneida was nevertheless trapped into the courtroom of Justice Ginsburg, because the City of Sherrill turned (not surprisingly) to legal channels. Paradoxically, contesting U.S. sovereignty has the effect of acknowledging it.

Specifically in our case, when the Court focuses on the time that has passed since the wrong that was done to the Oneidas – “grave, but ancient, wrong,” in Justice Ginsburg’s words – it presents us with an understanding of colonial invasion as an event. In the view of the Court, the wrong that was done to the Oneidas is grave, but ancient. It was done once and now it is over. It is not an ongoing wrong. But another view on colonial invention sees invasion as a structure, not an event. According to this view, the dispute in the City of Sherrill case is about the present, not about the past. Ginsburg’s reasoning masks this trait of settler colonialism. Furthermore, if we see colonial invasion as an event that took place long ago, and is now irrelevant to our case due to the doctrine of latches, then the reference made by Ginsburg to the “innocent purchasers” who now reside in Sherrill makes it seem as if it is not the Oneidas who needs the protection of the Court against the violation of its sovereignty (since this violation had happened in ancient times), but the settlers who in the present need protection from Indigenous reposession of their lands.

Justice Stevens’ dissenting opinion critiques the majority opinion thus:

In this case, the Tribe reacquired reservation land in a peaceful and lawful manner that fully respected the interests of innocent landowners – it purchased the land on the open market. To now deny the Tribe its right to tax immunity – at once the most fundamental of tribal rights and the least disruptive to other sovereigns – is not only inequitable, but irreconcilable with the principle that only Congress may abrogate or extinguish tribal sovereignty.

But as preferable as Stevens’ outcome is to Ginsburg, it, too, affirms the doctrine of discovery, Congress’s plenary power, and U.S. entitlement to Indigenous land. As political theorist Robert Nichols has argued, Native land became property only as it was stolen from Native peoples. Dispossession made land into property, and the doctrine of discovery legitimated dispossession. Through the doctrine of discovery, as it was applied to American lands by the Marshal court, Indigenous peoples in the United States “came to possess a proprietary right that could only be fully actualized in the moment of its extinguishment, that is, by transferring it to another” (Nichols, 117). For this reason, the Oneida’s attempt to regain control – property rights – over those lands seem preposterous. Sovereignty and property rights remain tightly connected in City of Sherrill, and the doctrine of discovery, which is sited in the first footnote in Ginsburg’s decision, remains unchallenged.

“Under the “doctrine of discovery,” … “fee title to the lands occupied by Indians when the colonists arrived became vested in the sovereign–first the discovering European nation and later the original States and the United States.”

Resources

SUGGESTED CITATION

Dana Lloyd, "City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York," Doctrine of Discovery Project (19 October 2022), https://doctrineofdiscovery.org/sherrill-v-oneida-opinion-of-the-court/.

Download citation formats:

Share on

X Facebook LinkedIn BlueskyDonate today!

Open Access educational resources cost money to produce. Please join the growing number of people supporting The Doctrine of Discovery so we can sustain this work. Please give today.