Gomeroi Native Title - Living in the Shadow of Terra Nullius Part 02

Part 2

Gomeroi Native Title - Living in the Shadow of Terra Nullius

Santos NSW Pty Ltd and Another v Gomeroi People and Another [2025] NNTTA 12

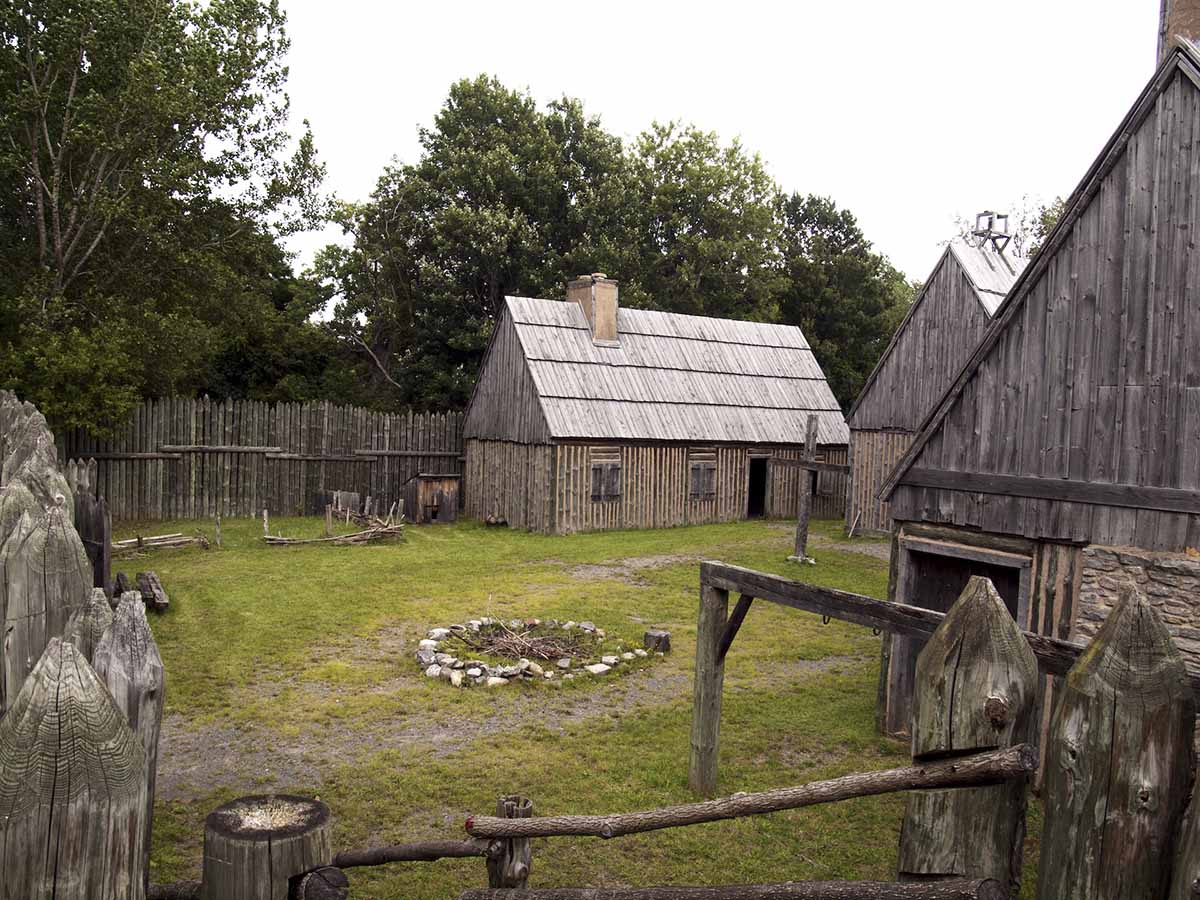

Photo supplied by Gomeroi Elder, Polly Cutmore

Photo supplied by Gomeroi Elder, Polly Cutmore

Abstract

This article is presented as a two-part series examining the structural limitations of Australia’s native title system and its entanglement with colonial legal authority, extractive capitalism, and the denial of Indigenous sovereignty.

Part 1 - Native Title and the Afterlife of Terra Nullius: Law as Containment, Not Recognition - examines the structural logic of native title as a continuation of settler-colonial domination rather than a pathway to Indigenous sovereignty. Through a critical reading of *Mabo v Commonwealth* (No. 2) [1992] HCA 23, native title jurisprudence, and the doctrinal legacy of *terra nullius, it argues that native title is not recognition but containment, a legal fiction that converts sovereignty into usufruct rights, enforced by state prerogative power. Drawing on thinkers like Carl Schmitt, Frantz Fanon, Edward Said, Patrick Wolfe, and Aileen Moreton-Robinson, it explores how Indigenous law is disfigured into cultural myth, and how recognition operates as a tool of regulation, not justice. Native title is exposed as the afterlife of terra nullius, the Crown’s fallback position that cloaks sovereign denial in the language of inclusion.

Part 2 - Gomeroi v Santos: Recognition Without Power, Law Without Sovereignty - applies the theoretical framework developed in Part 1 to the National Native Title Tribunal (NNTT) determination inSantos NSW Pty Ltd and Another v Gomeroi People and Another [2025] NNTTA 12(19 May 2025). The determination reveals how native title operates as a legal mechanism of containment, not empowerment. Despite the Gomeroi people’s overwhelming opposition to Santos’ Narrabri Gas Project, the National Native Title Tribunal authorised the licenses, demonstrating how cultural rights are acknowledged only to be overridden. The case exemplifies what scholars like Carl Schmitt, Giorgio Agamben, and Glen Coulthard describe: a legal system that recognises Indigenous presence while structurally excluding Indigenous power. Through concepts like prerogative sovereignty, the ‘state of exception,’ and the colonial logic of terra nullius, Part 2 shows that native title remains bound to a legal architecture designed to neutralise Indigenous law and uphold settler supremacy, even when cloaked in consultation and ‘public interest.’

Part 2 -Gomeroi v Santos: Recognition Without Power, Law Without Sovereignty

2.1: background - the decision and its implications

The Santos $3.6 billion Narrabri Gas Project starkly exposes the limitations of Australia’s native title system. Despite a near-unanimous vote by the Gomeroi people - 162 against, only 2 in favor - to reject the proposal, the National Native Title Tribunal authorised the granting of four petroleum production licenses for coal seam gas mining in the culturally significant Pilliga Forest. The project will extract gas from coal seams between 300 and 1,200 metres below ground, using up to 850 wells, along with refining facilities, gas and water processing, and associated infrastructure. The leases for such cover 95,000ha (368 square miles) (Maxwell and Kirby, SBS, NITV, 2025).

This decision highlights that native title does not confer a right to veto mining projects on Indigenous lands; rather, it offers a right to negotiate, which can be unilaterally overridden by the state if an agreement cannot be reached. Crucially, it confirms that ‘user rights’ under native title, such as maintaining cultural practices or caring for Country , cannot override extractive rights sanctioned by the settler state. Even when profound cultural significance is at stake, economic imperatives prevail. Native title, far from empowering traditional owners, often functions as a legal instrument of dispossession, masked by consultation but stripped of veto.

2.2: structural dispossession – dismantling the pilliga

The Gomeroi done everything settler law demands: they submitted detailed affidavits, mapped cultural information and impacts, bush food and medicine, recorded water knowledge and spiritual values, affirmed spiritual obligations to land and water, and explained complex cosmologies (judgement 19/05/2025 in passim). They have translated their sacred responsibilities into the procedural language of the Native Title Act. They even addressed scientific domains; greenhouse gases, agriculture, Waste Management, bushfire risk, and climate change impacts. They engaged in good faith (section 31 (1) (b) of Native Title Act 1993), within a system not designed to hear them as lawful authorities, but merely as cultural informants; users of the land, not owners.

The so-called ‘right to negotiate’ (section 31 (1) Native Title Act 1993) functions not as a safeguard, but as a means of pacification, giving the appearance of dialogue while ensuring the ultimate authority remains with the state. Thus: Aboriginal law can be acknowledged but not enforced; Spiritual harm can be measured but not prohibited; Indigenous sovereignty can be spoken but not acted upon. This is exactly what Agamben describes: the production of bare jurisdiction, where law is reduced to participation without power (Agamben, 1998, pp. 71-74).

2.3: theoretical frameworks in action

Here, Carl Schmitt’s theory of sovereignty becomes painfully clear. Sovereign is he who decides the exception (Schmitt cited in Antaki, 2004, pp.323, 325, 327). The Gomeroi have no capacity to enforce their law; their law is not allowed to decide. It is recognised, but only within a structure where recognition is not power. The Tribunal, backed by the state, holds the sovereign prerogative to decide when Aboriginal law matters, and more importantly, when it doesn’t. In this framework, Gomeroi law is permitted to speak, but never to compel. Every time Indigenous people get closer to touching that power, they move the goalposts. How many amendments have there been to the Native Title Act …hundreds?

The Tribunal acknowledges the magnitude and integrity of the Gomeroi’s evidence. It affirms the complexity and sincerity of their cultural law - ancestral creation, gendered ceremony, intergenerational responsibility. But this affirmation is procedural, not juridical. Culture enters the record, but it does not shape the outcome. Giorgio Agamben described this exact condition: the Indigenous subject is placed in a ‘state of exception’, recognised by the law but excluded from its protection and power (Agamben, 2005). The Gomeroi are made visible, but only so their law can be neutralised. As Irene Watson articulates, Aboriginal law is not incomplete; rather, it is rendered invisible by the settler state, which ‘recognises only what it can dominate’ (Watson, 2015, pp. 56–57). Their evidence is heard, but its force is stripped away. Indigenous law is included only as a cultural presence, not as a legitimate legal authority. Similarly, Audra Simpson asserts that recognition without the right to refuse is not justice; it is a performative act of inclusion that ‘requires Indigenous people to consent to their own dispossession’ (Simpson, 2014, pp. 1-36). The Tribunal’s procedures do not genuinely listen to Indigenous law; instead, they operate to nullify it through recognition devoid of meaningful consequence.

This is the design of the system, not its failure. Under section 39(1)(a) of the Native Title Act 1993* (nor any other section), the Tribunal cannot uphold Gomeroi law. It cannot enforce it. It can only assess harm and weigh it against the perceived public interest - an interest defined by extractive logic and settler capital. There is no veto for spiritual desecration. No mechanism to say no, even when Gomeroi law has already said *Gamil – no (Maxwell, 2024). There is only a checklist of considerations, Gomeroi ‘user’ interests among them, balanced against commercial interests and State-sanctioned development, where Aboriginal law is heard only so that the settler state can reaffirm its right to override it.

2.4: sacred law and bureaucratic management -** ontological and methodological conflicts

This legal architecture gives rise to a fundamental absurdity: in Gomeroi law, Country is indivisible, alive, ancestral. In settler law, it is fragmented and alienable, with lease areas, exploration corridors and buffer zones. Where the Gomeroi sees a single cosmological entity, the settler state sees a map of impacts to be managed. As Achille Mbembe argues, modern sovereignty often operates through necropolitics; the power to decide whose life is grievable, whose harm is calculable, and whose sacred obligations can be disregarded (Mbembe pp.11-40). Here, Gomeroi law is not just excluded; it is nullified through bureaucratic deference to extractive logic. Country is treated not as a living being, but as collateral - managed, mitigated, and mourned after the fact. Here again, Agamben’s insight is essential: the sacred is reduced to bare life, stripped of its lawfulness and treated as an object of bureaucratic administration. The Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Management Plan (ACHMP) (see judgement at paragraphs 231, 232, 236, 237, 413, 419) becomes the system’s answer to spiritual harm; an administrative spreadsheet applied to a cosmological wound that cannot be measured. The result is a collision of worldviews.

Two fundamental problems follow:

-

Ontological conflict - The law of the Gomeroi is Country: spiritual, indivisible and alive; Settler law demands its spatial and functional fragmentation, surveyed and assessed for risk. It demands abstraction, division, and quantification.

-

Methodological failure - The legal system cannot ‘see’ what the Gomeroi see; it does not have the epistemic tools to comprehend, let alone protect, what it has already dissected, reducing stories, spirits, and responsibilities into ‘cultural considerations’ - items to be weighed, not upheld.

The ‘upside-down river’ metaphor [judgement at 81 and 208] offered by the Gomeroi is not poetic embellishment, it is legal theory, and it is jurisprudence. It describes a world where water is not merely ecological, but sacred and juridical; where law flows not from the Crown, but from the land itself. The Gomeroi explained that these stories are not myths or beliefs - they are law. They encode ethical, legal, and territorial responsibilities. They mark restricted areas, gendered knowledge (judgement at 205), and ancestral presence (to name a few). Yet the Tribunal treats this material as symbolic, not juridical (judgement at 398 - 419). It is heard, but not authoritative. Sacred connections are acknowledged as culturally significant, but not as lawful limits on what the State or a developer may do. This is the colonial mechanism at work: to listen, but not yield; to include, but only in ways that disempower.

This is the pattern native title was designed to follow. Even when Gomeroi law is articulated clearly, and cultural harm is deeply evidenced, the process privileges settler priorities. Decision makers absorb Indigenous knowledge into frameworks that are structurally incapable of acting on it. The Tribunal weighs spiritual desecration against extractive benefit and ‘public interest’ and finds a way for the project to proceed - generally with ‘conditions’ or ‘offsets’ that do nothing to protect what has already been spiritually breached. Recognition becomes the mechanism of erasure.

2.5: recognition as erasure: the pattern of native title

In short, the Gomeroi did everything the law asked of them; they met every burden imposed by the settler system. But the law was never built to protect what they offered. It was built to validate extraction. The Futures Act regime does not function as a space of justice, rather, it functions as a filter, allowing culture to be heard while ensuring that development proceeds. The result is a systemic pattern: sing the song, show the map, speak the law - and lose anyway.

This is not a flaw in implementation; it is a feature of design. The Gomeroi evidence does not simply call for better outcomes within the existing system. It calls the system itself into question. It exposes a legal architecture that acknowledges without protecting, that hears without yielding, and that absorbs without transforming. It is a denial of sovereignty, and the lawful authority and obligations associated with it. What is required is not more consultation, more conditions, or more cultural heritage plans, but a rejection of the colonial logic that extraction is normal, and law is only what the Crown says it is.

Until Aboriginal law can govern Country again, until it is not just heard but obeyed, there will be no justice. Only recognition without power and sovereignty deferred in perpetuity.

2.6: the high cost of energy: what law sacrifices for ‘public interest’

Climate change was discussed in detail as was the ‘public interest’ in all issues associated with the matter (judgement paragraphs 85, 86, 167-170, 338-445). Regarding climate change and the known and potential impacts, the Tribunal made it clear:

It is not controversial that there is more than one source of greenhouse gas emissions, and more than one cause of global warming, and it would be an error for the tribunal to attribute every consequence of global warming to the proposed [Narrabri project] [judgement paragraph 170].

This exemplifies capitalism at its most basic, dispersing responsibility while centralising power. Its language sanitises extraction, externalises harm, and erases moral and ecological accountability by reducing the world to mere data points. It embodies the logic of the market: everyone is responsible, yet ultimately, no one is. This mindset stands in stark opposition to Indigenous stewardship and law, which is grounded in obligation, care, and a sacred interdependence with Country.

Moreover, the National Native Title Tribunal declared that:

the project is necessarily in the ‘public interest’, as all the gas recovered is for state domestic supply only.’ (judgment paragraph 357)

Here the state declares that it must act outside of normative legal regimes like native title or environmental protection because the situation demands it (e.g. energy crisis/economic need), and in doing so, renders Indigenous law and life exceptional, and outside the protection of rights (Agamben, 1998, Parts 2 and 3 in passim). For this to occur, Indigenous rights must be made invisible, so that something ‘lawful’ can happen. This isn’t just a legal failing, it is modern day colonialism dressed up in bureaucratic language like ‘public interest’ or ‘energy security.’

This erasure is wrapped in the language of ‘balance,’ ‘consultation,’ and ‘public interest’, but the real interest being served is profit. The claim that mining in places like the Pilliga forest is in the ‘public interest’ is a farce. Imagine drilling beneath the Vatican or the Sistine Chapel for economic gain. It would be unthinkable. Yet sacred Aboriginal sites, repositories of thousands of years of spiritual and ecological knowledge, are treated as obstacles to be overcome, not sanctuaries to be protected. This is modern-day colonialism, cloaked in bureaucracy.

What’s really happening is that the law continues to function as a tool of dispossession and degradation, cloaked in the neutrality of ‘balancing interests,’ when in truth, Indigenous rights and beliefs are treated as subordinate and expendable. The so-called balance always tips in favour of extraction, profit, and settler priorities - a façade of justice masking what is, in effect, a sanctioned regime of legalised lawlessness, as Bruce McIvor describes it.

2.7: the source - an act of supremacy

The Tribunal’s decision is more than just a legal ruling - it is a manifestation of the prerogative powers of the state. These are not neutral administrative powers; they are colonial remnants of the Royal prerogative - vestiges of Crown authority imported into Australia through the assertions of res nullius (pre-emptive non-justiciable sovereignty) and later terra nullius (mode of acquisition/containment) and later again, the Constitution. Prerogative powers, an exercise of divine rights, flow from the Act of Supremacy (1534) when Henry VIII declared himself supreme authority. Similarly, the ‘act of state’ doctrine relied on in Mabo v Queensland (No 2) (1992) is a modern-day reiteration of an ‘act of supremacy’, a non-justiciable prerogative power. With regards to resources, this legal lineage can be traced back to the *Case of Mines *(1568), a foundational English case that confirmed the monarch’s ownership of gold and silver and laid the groundwork for state control over sub-surface resources such as gas.

This assumed pre-emptive prerogative sovereign right to minerals and land was never agreed to, never negotiated, and never subject to any form of treaty or consent. It arrived by force, embedded in the colonial constitutional framework, which itself was constructed on the fabricated legal fictions of res nullius and terra nullius. The sovereign’s claim to land and subsoil wealth derives from the Royal prerogatives entrenched in the 1568 Case of Mines were imported wholesale to these shores, alongside terra nullius. These powers remain untouched by any true public reckoning, shielded from scrutiny by a veneer of legality, unquestionable - non-justiciable. The state still draws on that inherited power when it extinguishes or overrides Indigenous rights in the ‘public and national interest.’ A unilateral imposition - a system built on erasure, not inclusion.

As Glen Coulthard argues, settler recognition often functions not to include Indigenous peoples as sovereign equals, but to reinscribe their subordination within a legal-political framework that leaves the foundations of colonial authority untouched (Coulthard, 2014, Chapters 1, 4 and 5 in passim).

Conclusion

So, what did the 19 May Tribunal decision prove? That native title cannot stop extraction. It cannot protect Country. It cannot uphold Indigenous sovereignty. Because it was never meant to. Native title is not a step toward freedom; it is a cage of containment, constructed from law, dressed as justice, and maintained by the Crown. It is simply a modern extension of the same imperial logic embedded in the 1534 Act of Supremacy, which transferred spiritual and temporal domination from the Pope to the English Crown. The Tribunal’s ruling is not a break from that tradition - it is a continuation. Just another act of supremacy, reissued under new legal terms and its mask of engineered consultation, to assert control over Indigenous lands and deny Indigenous law. Whilst the names may have changed, the structure of domination remains intact.

Bibliography

-

Antaki, M. (2004), Carl Schmitt’s Nomos of the Earth. Osgoode Hall Law Journal 42.2: pp. 317-334 at http://scribd.com/document/847372113/Carl-Schmitt-The-Nomos-of-the-Earth-Telos-Press-Publishing-2006

-

Agamben, G. (1998) Translated by Daniel Heller Roazen, Homo Sacer, Sovereign Power and Bare Life, Stanford University Press at https://www.noinputbooks.com/endless/cc_06-27-11_07-23-11/Stanford%20University%20Press/1998/Agamben/agamben-giorgio_homo-sacer_1998.pdf

-

Agamben, G. (2005) Translated by Kevin Attell, State of Exception, University of Chicago Press at http://pdf-objects.com/files/US-English-PDF-Object.pdf

-

Alfred, T. Peace, Power, Righteousness: An Indigenous Manifesto (2009).

-

Blackstone (1765–1769), Commentaries on the Laws of England, Volume 2, Ch.1 @ https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/blackstone_bk2ch1.asp

-

Coulthard, G. S. (2014). Red skin, white masks: Rejecting the colonial politics of recognition. University of Minnesota Press at https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctt9qh3cv

-

Cox, Noel (2002, 2010) The Influence of the Common Law and the Decline of the Ecclesiastical Courts of the Church of England” [2002] ALRS 1; (2001-2002) 3(1) Rutgers Journal of Law and Religion 1-4 at http://classic.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/ALRS/2002/1.html#fnB102

-

d’Errico, P. P. (2022) Federal Anti-Indian Law, the Legal Entrapment of Indigenous Peoples, Bloomsbury.

-

d’Errico, P.P. (2025) Apache Oak Flat: Land is the Real Issue, Substack Article, at https://peterderrico.substack.com/p/apache-oak-flat-land-is-the-real?utm_source=post-email-title&publication_id=1314065&post_id=165290424&utm_campaign=email-post-title&isFreemail=true&r=1oz0tj&triedRedirect=true&utm_medium=email

-

Fanon, F. (1963) The Wretched of the Earth, translated by Constance Farrington, Penguin Books, 1963 (originally published 1961), p. 54 at https://monoskop.org/images/6/6b/Fanon_Frantz_The_Wretched_of_the_Earth_1963.pdf

-

Fanon, F. (2004) The Wretched of the Earth, translated by Richard Philcox, Penguin Books, 2004 (originally published 1961) at pp. 71 and 313 at https://dn790007.ca.archive.org/0/items/the-wretched-of-the-earth/The%20Wretched%20Of%20The%20Earth.pdf

-

Maxwell, R. 2024 Gamil means no: Gomeroi call on Santos to leave Pilliga, the Canberra Times at https://www.canberratimes.com.au/story/8549106/gamil-means-no-gomeroi-call-on-santos-to-leave-pilliga/

-

Mbembe, Achille. “Necropolitics.” Public Culture, vol. 15, no. 1, 2003, at pp. 11–40 at https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-15-1-11

-

Moreton-Robinson, A. (2015) The white possessive: Property, power, and Indigenous sovereignty. University of Minnesota Press, United States of America.

-

Said, Edward W. (1978) Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books, at https://monoskop.org/images/4/4e/Said_Edward_Orientalism_1979.pdf

-

Simpson, A. (2014) Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States, Duke University Press at https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv1198w8z .

-

Watson, I. (2007) ‘Aboriginal Women’s Laws and Lives: How Might We Keep Growing the Law’, The Australian Feminist Law Journal, vol. 26, pp. 95 - 109 at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13200968.2007.10854380

-

Watson, I. (2015) Aboriginal Peoples, Colonialism and International Law: Raw Law at https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/100961/9781317938378.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

-

Wolfe, P. “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native.” Journal of Genocide Research 8, no. 4 (2006): 387–409 at https://doi.org/10.1080/14623520601056240

-

Maxwell, R and Kirby, R (2025) Gomeroi people devastated by decision to allow Santos to mine coal seam gas in the Pilliga, SBS, NITV at https://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/article/gomeroi-gutted-by-decision-to-allow-santos-to-mine-coal-seam-gas-in-the-pilliga/4jew4d6b9?fbclid=IwQ0xDSwKb92xleHRuA2FlbQIxMQABHq87ejrPldKob3YImVVgHQQV3J9XqyviLAxQem0qhOmS_C96y5G_HvXQ7oXX_aem_qixRSRwB4Zr4cPHAbi_WAA

-

Miller, R. (2006), Native America, Discovered and Conquered: Thomas Jefferson, Lewis & Clark, and Manifest Destiny, Preager Publishers.

-

Newcomb, S. (2008). Pagans in the Promised Land: Decoding the Doctrine of Discovery. Fulcrum Publishing.

-

Newcomb, S. (2016) Property as a Right of Despotic Domination at https://ictnews.org/archive/property-as-a-right-of-despotic-dominion/

-

Newcomb, S. (2024) A View from the Shore, A Conversation with JoDe Goudy and editor Emily Sanna at https://issuu.com/ipjc/docs/a_view_from_the_shore_a_conversation_with_jode_go

SUGGESTED CITATION

Phil Rodgers-Falk, "Gomeroi Native Title - Living in the Shadow of Terra Nullius Part 02," Doctrine of Discovery Project (24 June 2025), https://doctrineofdiscovery.org/blog/gomeroi-native-title-living-shadow-terra-nullius-part-02/.

Download citation formats:

Share on

X Facebook LinkedIn BlueskyDonate today!

Open Access educational resources cost money to produce. Please join the growing number of people supporting The Doctrine of Discovery so we can sustain this work. Please give today.