Martin v. Waddell (1842) - Domination Translator Series - Part 7

In the Spring of 1835, William C. H. Waddell filed an “ejectment” lawsuit in the Circuit Court of the United States for the District of New Jersey. Waddell was suing to eject [remove] “Merrit Martin and others for the recovery of certain land covered with water, situated in the Raritan Bay, below high-water mark in the State of New Jersey. The defendants appeared to the suit, and at April term 1837, the cause was tried by a jury, which found a special verdict on which judgment was afterwards entered for the plaintiff…”

The dispute in this case had to do with one hundred acres of originally Lenape land covered with water and located in Raritan Bay, in Perth Amboy “in” the that part of Lenapehoking the colonizers refer to as the “State of [Domination called] New Jersey.” The [right of domination asserted to the] land being claimed lay beneath the navigable waters of the “Raritan River” and “Raritan Bay.” It was a location where the tide ebbs and flows. The main right in dispute was a right of property [domination] in the oyster fisheries in the public rivers and bays of East New Jersey.

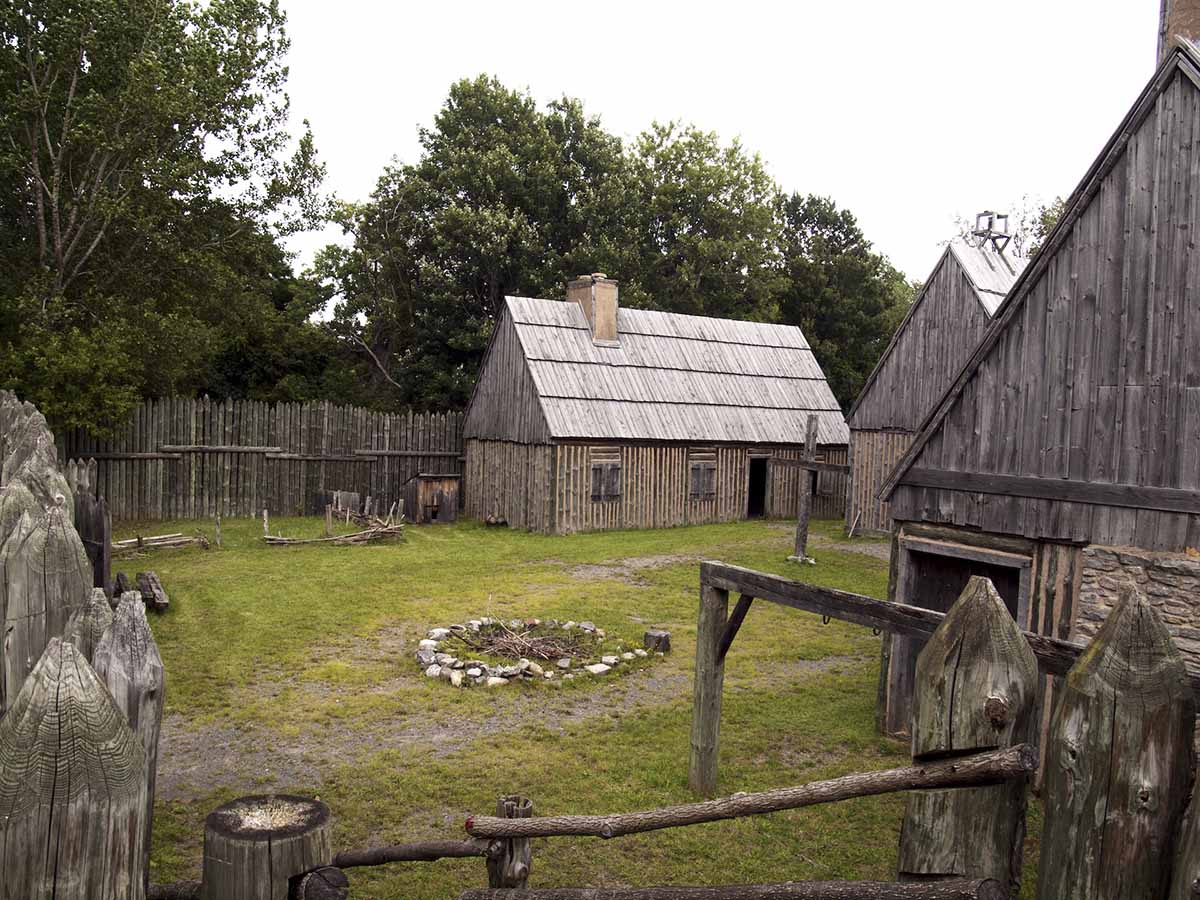

The claim of the right of property [domination] in the oyster beds in that one-hundred-acre area was made [by Waddell] pursuant to the royal charters issued [some one hundred seventy years earlier] in 1664 and 1674 by King Charles II to his brother, the Duke of York. The charters were issued by the king to the Duke of York “for the purpose of enabling him to plant a colony on the continent of [North] America.”

The area in controversy was located “within the boundaries of the charters, and in the territory which now forms” what is called “the State of New Jersey.” By a number of conveyances, the territory in the grant to the Duke of York “became vested in the proprietors of East Jersey.” They, in turn, “conveyed that area of land [‘the premises in controversy’] to the defendant, Mr. Waddell.

According to the terms of the grant given to them, the proprietors [presumed owners] were originally invested with all the rights of government and property [domination] which were conferred on the Duke of York. Later, in 1702, the proprietors handed all the powers of government to the Crown and retained the rights of private property. The defendant, Mr. Waddell, claimed the exclusive right to take oysters in that the area “granted to him by virtue of his title under the proprietors.”

The plaintiffs, “Martin,” were grantees from the “State of New Jersey,” under a law of that state that was passed in 1824, along with a supplement to that law. They claimed the exclusive right to take oysters in the place Waddell claimed that same right. The dispute between the parties came down to the interpretation and legal effect of the letters patent issued to the Duke of York, and the deed of surrender to the Crown made by the proprietors.

The syllabus of the case further states:

“The right of the King of Great Britain to make this grant to the Duke of York, with all of its prerogatives and powers of government, cannot at this day be questioned.” In other words, the Court would not inquire into a key and underlying question, specifically, “Did the King of Great Britain have the right to grant to the Duke of York the prerogatives and powers of government that he as the monarch of Great Britain purported to make in the aforementioned charters of 1664 and 1674?”

The syllabus continues:

“The English possessions in America were not claimed by right of conquest, but by right of discovery [and by the claim of a right of domination]. According to the principles of international law, as then understood by the civilized [dominating] powers of Europe, the Indian tribes in the new world were regarded as mere temporary occupants of the soil, and the absolute rights of property [domination] and dominion [domination] were held [assumed] to belong to the European nations by which [the location of] any portion of the country was first discovered [identified].”

“The [purported] grant [of a right of domination] to the Duke of York was not of [over and to] lands won by the sword, nor were the government and laws he was authorized to establish intended for a conquered people.”

The country granted by King Charles the Second to the Duke of York, was held by the King in his public and regal character, as the representative of the nation, and in trust for them. The discoveries made by persons acting under the authority of the government were for the benefit of the nation, and the Crown, according to the principles of the British Constitution, was the proper organ to dispose of the public domain. Cited, Johnson v. McIntosh, 8 Wheat. 595.

When the Revolution took place, the people of each state became themselves sovereign, and in that character held the absolute right to all their navigable waters and the soils under them for their own common use, subject only to the rights since surrendered by the Constitution to the general government. A grant, therefore, made by their authority must be tried and determined by different principles from those which apply to grants of the British Crown, where the title is held by a single individual in trust for the whole nation.

The [right of domination called] dominion and [the right of domination called] property in navigable waters and the lands under them [those waters] being held by the King as a public trust, the grant to an individual of an exclusive fishery in any portion of it is so much taken from the common fund entrusted to his care for the common benefit.

In such cases, whatever does not pass by the grant remains in the Crown for the benefit and advantage of the whole community. Grants of that description are therefore, construed strictly, and it will not be presumed that the King intended to part from any portion of the public domain unless clear and special words are used to denote it.

The rivers, bays, and arms of the sea, and all the prerogative rights within the limits of the charter of King Charles, undoubtedly passed to the Duke of York and were intended to pass except those saved in the letters patent.

The charter of King Charles issued to the Duke of York “is not a deed conveying private property, to be interpreted by the rules applicable to cases of that description. It was an instrument upon which was to be founded the institutions of a great political community, and in that light it should be regarded and construed.”

“The object in view of the letters patent appears on the face of them. They were made for the purpose of enabling the Duke of York to establish a colony upon the newly discovered continent, to be governed as nearly as circumstances would permit according to the laws and usages of England, and in which the Duke, his heirs, and assigns, were to stand in the place of the King and administer the government according to the principles of the British Constitution, and the people who were to plant this colony … were subjects of Great Britain, accustomed to be governed according to its usages and laws.”

The land under the navigable waters within the limits of the charter passed to the grantee as one of the royalties incident to the powers of government, and were to be held by him in the same manner and for the same purposes that the navigable waters of England and the soils under them are held by the Crown. The policy of England since Magna Charta – for the last six hundred years – has been carefully preserved to secure the common right of piscary for the benefit of the public. It would require plain language in the letters patent to the Duke of York to persuade the Court that the public and common right of fishing in navigable waters, which has been so long and so carefully guarded in England, and which was preserved in every other colony founded on the Atlantic borders, was intended in this one instance to be taken away. There is nothing in the charter that requires this conclusion.

The surrender by the proprietors to Queen Anne in 1702 was of “all the powers, authorities, and privileges of and concerning the government of the province,” and the right in dispute in this case was one of these privileges. No words are used for the purpose of withholding from the Crown any of its ordinary and well-known prerogatives. The surrender, according to its evident object and meaning, restored them in the same plight and condition in which they originally came to the hands of the Duke of York. When the people of New Jersey took possession of the reins of government and took into their own hands the power of sovereignty, the prerogatives and regalities which before belonged either to the Crown or the Parliament, became immediately and rightfully vested in the state.

Quaere. Whether on a question which depends not upon the meaning of instruments formed by the people of a state or by their authority, but upon the letters patent granted by the British Crown, under which certain rights are claimed by the state, on one hand, and by private individuals, on the other, if the Supreme Court of the State of New Jersey had been of opinion that upon the face of the charter the question was clearly in favor of the state, and that the proprietors holding under the letters patent had been deprived of their just rights by the erroneous judgment of the state court, it could be maintained that the decision of the court of the state on the construction of the letters patent bound the Supreme Court of the United States. The decision of the state court upon the letters patent by which the province was originally granted by the King of Great Britain is unquestionably entitled to great weight. If the words of the letters patent had been more doubtful, quaere if the decision of a state court on their construction, made with great deliberation and research, ought to be regarded as conclusive.

The defendant in error, the lessee of William C. H. Waddell, instituted, to April term 1835, in the Circuit Court of the United States for the District of New Jersey, an action of ejectment against Merrit Martin and others for the recovery of certain land covered with water, situated in the Raritan Bay, below high-water mark in the State of New Jersey. The defendants appeared to the suit, and at April term 1837, the cause was tried by a jury, which found a special verdict on which judgment was afterwards entered for the plaintiff [Martin], from which judgment, the defendants prosecuted this writ of error.

Cases

- Martin v. Waddell, 41 U.S. (16 Pet.) 367 (1842). https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/41/367

- Johnson & Graham’s Lessee v. McIntosh, 21 U.S. (8 Wheat.) 543 (1823). https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/21/543

Series Navigation

| Previous: The Monroe Doctrine (Part 6) | Next: President Teddy Roosevelt’s Monroe Doctrine Corollary (Part 8) |

Copyright

© Copyright Steven T. Newcomb, January 1, 2026

SUGGESTED CITATION

Steven T. Newcomb, "Martin v. Waddell (1842) - Domination Translator Series - Part 7," Doctrine of Discovery Project (7 January 2026), https://doctrineofdiscovery.org/blog/domination/martin-waddell/.

Download citation formats:

Share on

X Facebook LinkedIn BlueskyDonate today!

Open Access educational resources cost money to produce. Please join the growing number of people supporting The Doctrine of Discovery so we can sustain this work. Please give today.