The Domination Translator Series: An Extended Essay on Various U.S. Supreme Court Rulings and Other Topics - Part 1

Introduction and Setting the Context for The Domination Translator Series: An Extended Essay on Various U.S. Supreme Court Rulings and Other Topics

As scholars, we face a central challenge in our efforts to understand and explain the ideas and arguments that the United States government has applied to the original Native nations and peoples of this Turtle Island continent (“North America”). Part of that challenge consists of attempting to accurately interpret how representatives of the U.S. government have thought and written about the political identity of our Native nations, and about the relationship between our nations and the political system named The United States of America.

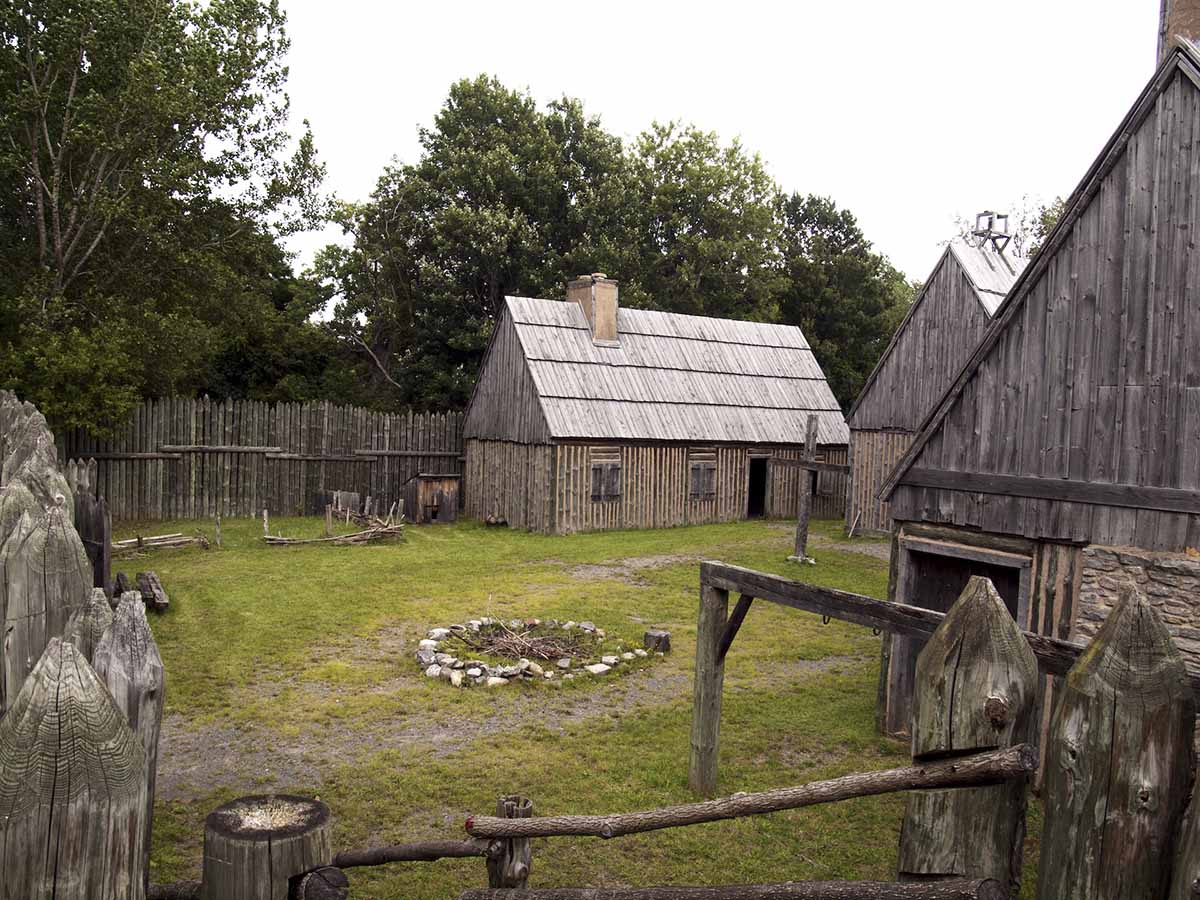

As a starting point, we are well advised to begin by setting the context within which to engage in our efforts. A good place to begin is by acknowledging the free and independent existence of the Native nations of this continent prior to the arrival of ships traveling westward across the Atlantic Ocean from a faraway geographical place called Western Christendom (Western Europe). Next, we need to reflect upon the contrast between the free way of life of our Native nations and the Christian Europeans’ mental world and system of domination that was transported by ship from Western Europe and imposed on everyone and everything here on Turtle Island and throughout this hemisphere that is located to the west of Western Europe.

With those two perspectives in mind, we must add two more. The first is the imagined viewpoint of our free Native ancestors standing on the shore looking at the colonizing ships sailing toward them. The second perspective is that of the colonizing people standing on the deck of any of those ships, looking toward our Native ancestors, with the intention of mentally and linguistically imposing their words, ideas, arguments, and behaviors on our Native ancestors and on their traditional lands, waters, and ecological systems.

A Brief Lexicon of Domination

There are specific words that serve as carriers of the paradigm of domination. They all tacitly (in a hidden manner) presume a right of domination. The terms include:

1) “Civilization” (not as a noun but, as a gerund or operating process) (i.e. “the forcing of a cultural pattern on a population to which it is foreign,” says Webster’s Third New International Dictionary);

2) “State,” “a relation of men dominating men,” says Max Weber in his 1919 essay “Politics As A Vocation.1 “if the state is to exist,” he continues, “the dominated must obey the authority claimed by the powers that be,” says Max Weber.2

3) “Sovereignty,” “an unjust form of political domination that limits human freedom,” writes Jonathon Havercroft in Captives of Sovereignty.3

4) “Ascendancy,” (“controlling influence, governing power, domination,” says Websters Dictionary;

5) “Dominion” (is traced back to the Latin term “dominium,” which means domination says William Brandon in New Worlds for Old);4

6) “Property,” “despotic dominion,” says William Blackstone in his Commentaries on the Common Law;

7) “Empire,” “an imperium—a dominion [domination], state [domination], or sovereignty [domination] that would expand in population and territory and increase in strength and power,” writes Richard Van Alstyne);5

8) “Government,” “rule, sway.” The term “ment” = “a state or condition of” + “to go” + “over” are embedded in the word “go-over-n-ment” (The Carnegie Institution editors of European Treaties Bearing on the History of the United States, Vol I, translated the Latin word “dominationes” (dominations) into the English word “governments,” thereby drawing a connection between the two terms).

Each of the above words is a synonym for and carrier of the paradigm of domination. The average person was never taught to understand these words as having anything to do with domination. As soon as the seafaring colonizers from Christian Europe (Christendom) made landfall here on this continent centuries ago, they began using those and other words to create and maintain a system and coercive process of domination throughout the geographical space that they as foreign voyagers had newly identified and over which they were determined to exert their will and absolute control.

Newcomb’s Domination Translator

The vast tapestry of information in the background of particular words and terminologies typically remains out of focus. Newcomb’s Domination Translator, already applied to number 7 above, is one technique for bringing into the foreground of our awareness that background dimension of meaning. If we know, for example, that the eight words in our Lexicon are examples of domination, there is a simple method for bringing this connection to the attention of the reader while bringing an awareness of the background dimension into the foreground. The following are two examples of this technique: “civilization [domination],” and, “the state [of domination].” This technique will be used frequently throughout this essay.

The American Empire [Domination]

The U.S. Supreme Court has on two occasions declared the United States to be the American empire. First time in Loughborough v. Blake (1820) and again in Downes v. Bidwell (1901). The documents, history, and U.S. Supreme Court decisions we will be summarizing in this essay ought to be read with the understanding that what is typically termed “The United States of America” is also accurately understood as “the American system of domination.” The men who are typically known as “the Founders” of the United States were conscious of the fact that they were founding an empire. They were breaking away from the British Empire in order to found their own American Empire.

In his book The Rising American Empire, historian Richard Van Alstyne examines in passing some ideas of Benjamin Franklin: “Benjamin Franklin, who learned at least some of his Roman history from Machiavelli’s Discourses, regarded first the British Empire, and then the American, as Roman in conception, and he used the word ‘national’ and ‘imperial’ interchangeably. His [Franklin’s] imperium was Augustan [i.e. referencing the Roman Emperor Augustus], but even more he stressed an expanding empire [domination] in territory and population.” (p. 2).

The American founders were men who understood the need for linguistic subtlety. Van Alstyne quotes Julius W. Pratt as stating, “in reality, the extension of American rule [domination] over Indian tribes and their lands was imperialism—not recognized as such only because the Indians were so few in number as the be virtually swallowed.” Van Alstyne continues by noting: “Here it might be pointed out that American foreign policy has a vocabulary all its own, consciously—even ostentatiously—sidestepping the use of terms that would even hint at aggression or imperial domination, and taking refuge in abstract formulae, stereotypical phrases, and idealistic clichés that really explain nothing.” (p. 7)

Van Alstyne expands upon this point as follows: “Phrases like ‘Monroe Doctrine’, ‘no entangling alliances’, ‘freedom of the seas’, ‘open door’, ‘good neighbour policy’, ‘Truman doctrine’, Eisenhower doctrine’, strew the pages of American foreign policy.” American foreign policy masterfully hides the claim of a right of imperial domination behind neutral, even positive sounding terms.

As Van Alstyne puts it: “Parrot-like repetition of these abstractions and other generalities produces an emotional reflex which assumes that American diplomacy is ‘different’, purer, morally better than the diplomacy of other powers.” He adds:

Consider, for instance, the implication behind the well-worn stereotype, ‘The United States enforces the Monroe Doctrine’. My dictionary tells me that a doctrine is a teaching—its derivation is the Latin verb doceo, ‘I teach’ . But actually as American diplomacy manipulates this phrase, the Monroe Doctrine has long since assumed the characteristics of positive law which the United States, the lord [dominator] of the western hemisphere, applies from time to time as it sees fit. The particular application may or may not be benevolent—that depends on how it is interpreted; but there is no doubt that it is arbitrary. Furthermore, it is an interesting point, I think, that American diplomacy shows a preference for a term that is commonly identified with theological dogma. The Monroe Doctrine has the additional authority of Canon Law behind it. To carry the analogy further, the United States assumes unto itself a function of the mediaeval Papacy, the prerogative of infallibility.

The quotation, ‘wheresoever the Roman conquers, he inhabits’, which is incorporated in the title of this first chapter, is from the Stoic philosopher, Seneca. I culled it from the pages of one of the greatest historians, Edward Gibbon, in the opinion that it applies with equal truth to the American nation. The idea that America—the ‘New World’—would be conquered [dominated] and inhabited by people of English stock was native to the empire builders of Elizabethan England and bred into the minds of the early immigrants to Virginia and Massachusetts Bay. With the latter, especially with the Puritans who migrated with a sense of grievance against their homeland, it became an article of faith that they were in a new world, a new sphere.

Puritans, who regarded themselves as founders of a new Israel in the North American wilderness, the doctrine that the two spheres became a fixation in the American mind prerequisite to the growth of nationalism. New England, which was ‘God’s American Israel’ according to its Calvinistic divines, assumed from the outset an attitude of political independence toward the mother country. The Great and General Court of Massachusetts—the pretentious title which the legislative assembly of that province bestowed upon itself—audaciously substituted an oath of allegiance to itself in place of the oath to the king (pp. 7-8).

Looked at from the standpoint of the sum total of its history, the abstract formulae and principles being disregarded or at least discounted, the United States thus becomes by its very essence an expanding imperial power. It is a creature of the classical Roman-British tradition. It was conceived as an empire; and its evolution from a group of small, disunited English colonies strung out on a long coastline to a world power with commitments on every sea and in every continent, has been a characteristically imperial type of growth (p. 9).

My reason, then, for invoking the heretical phrase, American empire, is so that the United States can be studied as a member of the competitive system of national states, with a behaviour [sic] pattern characteristic of an ambitious and dynamic national state. This approach gives precedence to foreign affairs over domestic affairs, reversing the customary practice of treating national history from the standpoint of the nation preoccupied with its own internal affairs and only incidentally looking beyond its borders. In other words, it is a history of the American national state or, as I prefer, of the American Empire, rather than a history of the American people (pp. 9-10).

With the above context in mind, we can now begin to examine a number of U.S. court rulings and significant historical milestones in U.S. history, and in the history of U.S. anti-Indian law and policy.

Series Overview

The 15-part series begins with an introduction and proceeds chronologically through key legal decisions:

-

Introduction: The Domination Translator Series — An overview of the series and its methodology

-

Fletcher v. Peck (1810) — The first Supreme Court case to reference the Doctrine of Discovery

-

The Marshall Trilogy: Johnson v. McIntosh (1823) — Chief Justice John Marshall’s foundational ruling establishing discovery doctrine as U.S. law

-

The Marshall Trilogy: Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831) — Defining indigenous nations as “domestic dependent nations”

-

The Marshall Trilogy: Worcester v. Georgia (1832) — Affirming tribal sovereignty while maintaining discovery doctrine supremacy

-

The Monroe Doctrine (1823) — Extending discovery principles to hemispheric policy

-

Martin v. Waddell (1842) — Applying discovery doctrine to property rights and tidelands

-

President “Teddy” Roosevelt’s Monroe Doctrine Corollary — The expansion of imperial authority based on discovery principles

-

Tee Hit Ton Indians v. United States (1955) — Denying aboriginal title under discovery doctrine

-

White v. University of California (9th Circuit, 2014) — Modern application of discovery doctrine in higher education policy

-

The Haudenosaunee Cases: Cayuga Indian Nation v. Pataki (2005) — Examining discovery doctrine in contemporary land claims

-

The Haudenosaunee Cases: Oneida Indian Nation v. County of Oneida (2010) — Persistent barriers to indigenous sovereignty rooted in discovery doctrine

-

The Haudenosaunee Cases: Onondaga Nation v. New York (2012) — Environmental justice and the limits of discovery-based law

-

McGirt v. Oklahoma (2020) — A landmark decision recognizing the Creek Nation’s reservation despite discovery doctrine precedent

-

U.S. v. King Mountain Tobacco Co., Inc. (9th Circuit, 2012) — Tribal sovereignty and the limits of federal authority

Series Navigation

Next: The Marshall Trilogy: Fletcher v. Peck (Part 2)

Copyright

© Copyright Steven T. Newcomb, January 1, 2026

Footnotes

-

From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, Translated, Edited, And With An Introduction By H. H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills, (Oxford University Press: New York, 1946), p. 78. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Jonathon Havercroft, Captives of Sovereignty (Oxford University Press?, New York, 2014, p. 34). ↩

-

William Brandon, New Worlds for Old: Reports from the New World and their Effect on the Development of Social Thought in Europe, 1500 to 1800, Athens, OH: University of Ohio Press, 121. See particularly the section titled “Dominium, which Brandon concludes: “Political power grown from property—dominium—was, in effect, domination. (What good is power if you can’t abuse it, runs a Sicilian proverb).” ↩

-

Richard Van Alstyne, The Rising American Empire, p. 1. ↩

SUGGESTED CITATION

Steven T. Newcomb, "The Domination Translator Series: An Extended Essay on Various U.S. Supreme Court Rulings and Other Topics - Part 1," Doctrine of Discovery Project (1 January 2026), https://doctrineofdiscovery.org/blog/domination/domination-translator-series-introduction/.

Download citation formats:

Share on

X Facebook LinkedIn BlueskyDonate today!

Open Access educational resources cost money to produce. Please join the growing number of people supporting The Doctrine of Discovery so we can sustain this work. Please give today.